The Travel & Tourism Academy, created by education non-profit Good Work Foundation (GWF), offers subsidised career training to young Mpumalanga residents who are passionate about contributing to the province’s tourism, hospitality and conservation economy, which they refer to as “the economy of wildlife”.

Conservation in Africa is everyone’s business, and tapping into rural communities’ innate understanding of natural heritage and wildlife is not only for the sustainable development of the continent, but also for the sector’s rich potential for employment.

The academy has seen great success so far, with at least 95% of its graduates employed in decent, meaningful jobs in lodges, private game reserves, hotels and other establishments, mainly in and around the Kruger National Park.

This comes as reassuring at a time when the country’s official employment rate has risen to 32.9% – a statistic that is generally far worse in rural areas, where anecdotal accounts say that every employed person is financially responsible for, on average, up to 14 people.

Having access to area-specific vocational training means that young rural people can study and ultimately work close to where they reside. They no longer have to move to cities in search of employment.

Local knowledge is lekker

“Game lodges would like to ‘employ local’,” says Kathleen Hay, GWF’s Travel & Tourism Academy programme manager.

“In the areas where campuses are based, there are few opportunities to study for a career in hospitality or conservation that are actually accessible by adjacent communities (both geographically and financially). Lodge managers have often said to me they would like to grow their staff complement coming from communities on the park’s border.”

Hay says the Conservation Academy, based at GWF’s Hazyview Digital Learning Campus, aims to get young people living near the Kruger National Park work-ready to be employed as guides. “The academy is plumb in the middle of one of the country’s biggest tourism hotspots, and with that comes opportunities for employment in our area. You could say we’re growing our own timber.”

“Parallel to the employment value is the conservation and education value, which is critical to understanding our wildlife heritage – recognising the incredible richness of the area and developing a love for it and a desire to preserve it.”

She says game lodges are also keen to benefit from the intrinsic knowledge held by locals – which means academy graduates who have grown up with an affinity for the bush and, often, a natural tracking ability are in demand as rangers and field guides. This adds depth to any visitor’s safari experience, says Hay.

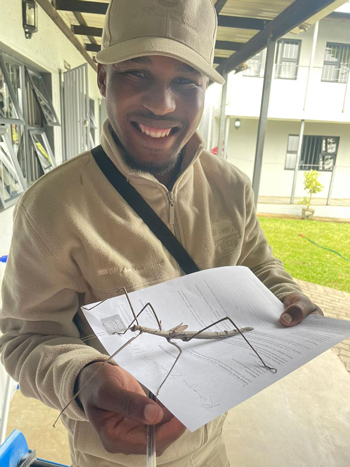

A case in point is GWF Conservation Academy 2022 alumnus Amend Mhlanga, who is currently enrolled in field guide training at the More Field Guide College. During a recent assessment at the college, he crafted a whistle flute (called xiwhewhe in Xitsonga) from the dried shell of the fruit from a black monkey orange tree – demonstrating a deep connection with the land and its natural treasures.

Opening eyes and changing lives

“The students don’t always know they have this indigenous knowledge, or understand the significance of it and how it’s an integral part of our heritage. But I’ve seen a great transformation in most of our students and graduates as they come to understand what it truly means to conserve the natural environment,” comments Conservation Academy coordinator Sibusiso Mnisi.

“Their eyes are opened to the impact of the crisis of rhino poaching, how trees can be used in a sustainable way, and what careers they can pursue. It’s a great life-changing experience for young people living around the Kruger National Park.”

Says Mhlanga, who was awarded a bursary through the More Community Foundation, “I grew up in the village of Newington near the Kruger Park. What inspired me to become a field guide was being out with my dad in the bush. He was a field guide and used to take me out with him. He taught me about interactions between animals as well as between people and wildlife, and about respecting our natural environment.”

Recognising his passion, Good Work Foundation encouraged him to study to be a field guide. “I have learnt the power of taking small steps and that change is good,” says this go-getting trainee field guide.

After completing the one-year academy programme, conservation students can study further to become trail guides, intern at lodges or private game reserves, or get corporate-sponsored work placements. “Once they have that under the belt, generally, they fly from there,” says Hay.

And they are thriving – including several female graduates who are busting the stereotype that wildlife conservation is a man’s job.

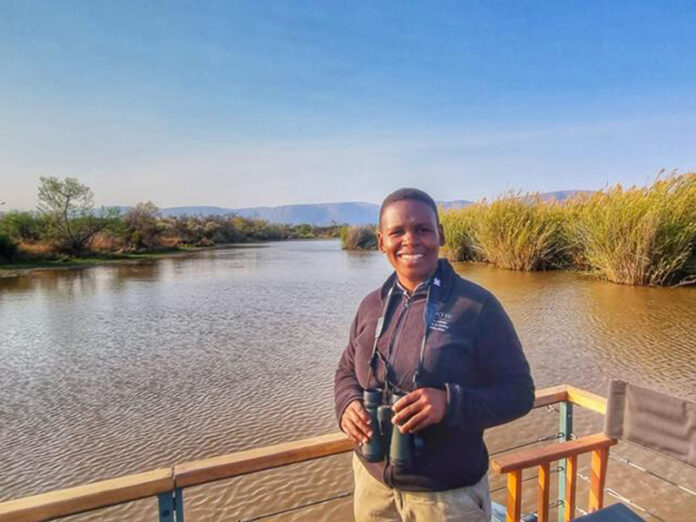

Graduate Joyce Maile is an apprentice field guide at the Lion Sands Game Reserve, part of Sabi Sands Game Reserve. She is grateful for the doors opened by the conservation programme, which she says “inspired me to be a better person, pushed me to see a vision for myself and helped me achieve my goals as a nature guide.

“They encouraged me to see the environment in a different way; I have a very different perspective now. Nature guiding was always seen as a man’s job, but I have always loved being in nature and believed I could become a field guide. I am strong and fearless!” she says.

Building conservation awareness with ‘school safaris’

Some students have never experienced the Kruger – despite growing up on the outskirts of the park. This is where the Conservation curriculum run by GWF’s Open Learning Academy, including its Sabi Sands Schools Safari and Coaching Conservation components, comes in.

“The children are like sponges – you really can’t underestimate the power of just being able to show them the park, and have them recognise and appreciate what wildlife conservation is all about,” says Hay. “And then we take that a level further with the Conservation Academy, giving young adults the skills to be meaningfully employed in that industry.”

Importantly, Conservation Academy graduates are paying it forward in their communities with that newly acquired knowledge, says Mnisi. One former student gave a talk about conservation to students at GWF’s Huntington Digital Learning Campus on Heritage Day, and another was recruited by a local primary school to teach learners about the natural environment.

“Ownership is key,” reflects Hay. “We have evolved from the notion of communities being beneficiaries of goodwill from the parks. The tide is changing completely, not just in South Africa, but in Africa in general, where the emphasis is now far more on custodianship of wild spaces and participation in their conservation.”

This underscores the importance of nurturing local communities’ innate passion for their natural surroundings and equipping them to make a living from it. Says Mnisi, “If we can foster that holistic understanding of how everything is interconnected, then we’ve done our job.”